The Look of Dune

Dune is a space epic set 10,000 years in the future that blends medieval and sci-fi aesthetics. The film is an adaptation of the 1965 Frank Herbert novel. The plot follows the 15-year old Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet) and House Atreides as they accept the stewardship of the desert planet Arrakis which carries the universe’s most precious resource known as Spice Melange. Meanwhile, Paul is trained by the personal guard of his father Duke Leto (Oscar Isaac), and his mother Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson), an acolyte of the Bene Gesserit, a powerful sisterhood who possesses psychic abilities. The challenge for Director Denis Villeneuve was taking such a long and detailed story and adapting it cinematically. This is the story of how he overcame such challenges. This is The Look of Dune.

In previous films, Villeneuve established a team of go-to artists crucial to achieving his vision. For Dune, he continued his collaboration with the likes of Patrice Vermette, Joe Walker, ACE, Paul Lambert, and Gerd Nefzer.

In an interview with frame.io, Walker remarked on the growing collaboration and compared them to a “well-rehearsed band” akin to “the days of Frank Zappa” because over the years they’ve picked up their favorite members and continue to tour with them.

Featured Department Heads

- Director: Denis Villeneuve

- Cinematographer: Greig Fraser

- Editor: Joe Walker, ACE

- Lead Digital Colorist: David Cole

- Production Design: Patrice Vermette

- Set Dec: Richard Roberts, Zsuzsanna Sipos

- Costume Design: Bob Morgan, Jacqueline West

- Art Direction: Tom Brown (supervising art director)

- Visual Effects: Paul Lambert

- Special Effects: Gerd Nefzer

The film and TV rights for Dune were acquired by Legendary Entertainment in 2016.

Technical Specifications

- Runtime: 2 hr. 35 min (155 min)

- Color: Color

- Aspect Ratio: 1.43 : 1 (IMAX Laser: some scenes), 2. 39 : 1 (Blu-ray release: some scenes), 1.90 : 1 (Digital IMAX: some scenes), 2.39 : 1.

- Camera: Arri Alexa LF IMAX, Panavision H-Series and Ultra Vista Lenses

- Arri Alexa Mini LF IMAX, Panavision H-Series and Ultra Vista Lenses

- Laboratory: FotoKem Creative Services, Burbank (CA), USA (digital intermediate)

- FotoKem nextLAB (digital dailies)

- Negative Format: Codex

- Cinematographic Process: ARRIRAW (4.5K) (source format)

- Digital Intermediate (4K) (master format)

- Panavision (anamorphic) (source format)

- Printed Film Format: D-Cinema (also 3-D version)

- DCP Digital Cinema Package

- Video (UHD)

●Adapting A Novel○

Arguably the world’s best-selling science fiction novel, millions of fans suffered numerous attempts to adapt Dune’s complex narrative. The source material was originally considered unfilmable and those who previously attempted to do so, like David Lynch in 1984, suffered the wrath of the critics.

Even though Villeneuve himself was a fan of the novel, he knew that he had to make a film that the layperson like his mother could watch and enjoy. The novelization of Dune is a long and complex tale full of exposition, numerous subplots, four appendices, and a glossary. Simply put, you can’t keep it all.

Within the medium of cinema, directors must make decisions to contain the story within 2-3 hours. By bottling the epic into two movies, it gives Villeneuve and his team a little more breathing room to set up the story and focus on constructing the world and its characters.

Dune is many things. It’s a coming-of-age tale; an epic with an empire at war; an environmental and political allegory. It’s such features that cinematographer Greig Fraser notes open the complex story to interpretation.

“I think a very typical cinematic thing is simplicity and economy. We were looking for that in the cut, but also paying our dues to the book.” -Joe Walker, frame.io

The Director’s Vision

The film’s producer Mary Parent told Deadline that there are only a few working directors today that could make a film feel as intimate as it does epic, and Villeneuve is one of them.

But not everyone was so certain. Editor Joe Walker was first told about the project while working on Blade Runner 2049 and was given the book by Villeneuve. After he read it he thought that the director had “bitten off a lot.”

PHOTO CREDIT: CHIABELLA JAMES

PHOTO CREDIT: CHIABELLA JAMES

But Villeneuve proved Parent’s words prophetic. For every day they would shoot an action sequence with Carryalls, there would be a week of intense character drama, according to Fraser.

“He understands that no matter how big the explosions and set pieces are if you don’t have the story straight the audience will walk out feeling empty.” -Greig Fraser, IBC

Selecting Storytelling Terms

There are plenty of sci-fi epics and yet nothing quite like Dune. There was no easy baked-in recipe. Villeneuve and his team had a few references but the novel was their primary source.

Walker was in a constant tug-of-war between the duration of the film and still finding time to establish the world. He opted to lean toward world-building.

“You could cut that out,” Joe Walker explains to Steve Hullfish of frame.io about a scene that introduced two symbolic palm trees, “but you’d lose the depth, the storytelling, and the world-building. I don’t think I’ve seen any other film that has got this level of world-building. As an editor, it would just be foolish to disregard that.”

A Time Paradox

However, this concept of time wasn’t so cut and dry. When piecing together the film later in post-production, Walker contended with a time paradox. Specifically, when it came down to how long it should take Paul to arrive on Arrakis.

“Sometimes shorter doesn’t necessarily feel shorter. Shorter duration doesn’t necessarily mean that the flow of the film improves. Sometimes, but I think the more important thing is what’s compelling, and that’s the imperative in storytelling terms.” -Joe Walker, SlashFilm

PHOTO CREDIT: CHIABELLA JAMES

The setup was the key to the payoff. Walker invested his time introducing Paul Atreides, his home planet, and his family and close comrades. That way, when the time comes for turmoil, you’re invested in them.

Walker believes some choices are purely aesthetic over anything else. Maybe they add to the world or give us insight into a specific culture, but sometimes there’s no payoff.

“You wouldn’t necessarily introduce a gun in act one, not to see it used in act three, but we have that. It’s part and parcel of setting up the Fremen culture. It’s not the gun, but it’s a crysknife. You set it up quite early. But that specific crysknife, we never see again. I don’t think that’s a flaw in the film or the book. I think it’s just the nature of the differences between novels and films.” -Joe Walker, SlashFilm

●The World○

The filmmakers behind Dune not only had a world to build but multiple planets and civilizations. It was production designer Patrice Vermette and a storyboard artist who first inspired Villeneuve and his development of the look.

Caladan, the home planet of the Atreides, is rich and lush whereas the Fremen’s home of Arrakis is incredibly hot and dry. The Harknonnen’s Giedi Prime is dark and heavily industrialized.

GIEDI PRIME, DUNE MOVIE WEBSITE

Typically, the bigger the budget, the more attention you can pay to world-building. Dune may appear on par with Marvel films, but it was working with a still big, yet more modest $165 million budget by comparison.

World-Building > Duration

The film takes its time in each environment allowing the audience to immerse themselves within the world. Such world-building moments could serve as helpful asides to the plot.

For instance, in the aside with the two palm trees in Arrakis that the Fremen keep alive with water as a reminder of a time when their planet was lush.

This is a moment that speaks to Fremen concepts and their rich cultural history. When the palm trees burn as collateral damage during the coup, it articulates the Fremen’s futility at the hands of imperialism.

COURTESY OF WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT/LEGENDARY PICTURES

The film set the tone early for the Fremen culture and Arrakis with a battle scene during the opening sequence. In addition, the culture is explored in books read by Paul and through a tour guide with the editor Joe Walker lending his voice.

Cinematographer Greig Fraser reminisced with IBC about his favorite moment in the film involving Paul:

“He arrives on a mission with his father and crew and when he steps out it’s him experiencing that sand for the first time. It’s such a simple idea but feeling this tactility for me was telling of his character. It foreshadows Paul’s connection to this land.”

There were also scenes that added dimension to the history of House Atreides, like the sculpture of the bull and alluding to the grandfather who was killed by the charge. This reveals a defining trait of the Atreides lineage and their steadfast nature even in the face of death.

Part of what Walker appreciates in working with Villeneuve is his chance to work with “brainstemy images,” meaning how these sensory images satisfy the most primal part of the brain. Just like the bull, it harkens back to ancient civilizations like the Minoans.

Minoan Bull-Leaping Fresco

●Wardrobe○

The scale of Dune surpasses multiple planets with Caladan, Giedi Prime, and Arrakis. Each planet is exceptionally different from the others with its own complex inhabitants, cultures, histories, militaries, customs, and politics. This was a tall order for one lone costume designer, which is why Jacqueline West teamed up with her close friend and fellow co-designer Bob Morgan.

COURTESY OF WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT

Designing at Scale

A team of nearly 200 artists was enlisted in the wardrobe department to craft hundreds of costumes. Costumes were constructed in Spain, London, and Budapest. In fact, four full-time shops were established in Budapest which included a sewing department, textile shop, aging department, armory dye shop, and prop department.

“It’s one thing to have one person standing there, it’s another thing to have 200 people standing there. I remember the day we lined up the Harkonnen soldiers, for the first time in the uniform in the dark, wow…. We had replicated 200 of them by standing in line or marching through the set in formation.” -Bob Morgan, SlashFilm

Morgan’s experience with capes on Man of Steel and Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice was invaluable to understanding what materials to use for Dune. He not only knew what fabrics were light enough to catch the air but heavy enough so it was just right. They used fans in their workshop to test their fabrics.

PHOTO CREDIT: CHIABELLA JAMES

History Informs the Future

For a story that takes place 10,000 years in the future, Villeneuve along with West and Morgan felt they had to look backward in order to predict the future. The author Frank Herbert originally based his interstellar civilization on medieval feudal courts. So, they wanted to avoid sci-fi tropes like silver gadgets and alien races.

SET PHOTO: GREIG FRASER

Their focus turned away from Hollywood’s sleek interpretation of the future in place of alchemy and tarots. Morgan even felt a connection to Greek tragedy where he associated House Atreides with the house of Atreus. “Our references were primarily historical,” Morgan told Vogue, “and Denis loved that.”

The Feast of Tantalus, Jean-Hugues Taraval

The Atreides, Fremen & Harkonnens

The planets and their features helped dictate the style of their wardrobe, and the film’s costume designers triangulated upon “these opposing worlds” and where they “were going to intersect,” according to Morgan.

PHOTO CREDIT: CHIABELLA JAMES

The wet and lush Caladan influenced the vibrant colors and richness of the fabric. They chose green as the primary color and modeled the Atriedes’ uniforms after another imperial family with a grim fate—the Romanovs.

Photograph of Romanov family

“We wanted to show they’re coming from a place of age and richness and moisture and grain, oceans and wealth and establishment.” -Bob Morgan, SlashFilm

By contrast, Arrakis was reminiscent of deserts like Jordan and the Saharas and the team turned to garments like face and body wraps that had functional purposes and could be utilized to cool its wearer down or be repurposed as a rope.

DUNE MOVIE WEBSITE

DUNE MOVIE WEBSITE

The black and leather uniforms of the evil environment-devouring Harkonnens were inspired by the Goths. Whereas, the Bene Gesserit were mysteriously veiled and adorned rich, black velvet and silks that obscured both them and their intentions.

Stillsuits

The iconic stillsuits of Dune are full-body suits designed for the harsh desert environment of Arrakis. What makes these suits so integral to survival is how they repurpose bodily fluids into drinking water. Morgan noted that a key challenge was designing stillsuits that looked functional while also allowing the actors to easily perform their choreography.

COURTESY OF WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT

In Herbert’s novel, he describes the stillsuits as the color of rocks. While the location department was visiting Jordan, they collected samples of sand and rocks from each location for the wardrobe department. That way, West and her team could see how the different sands would look on the stillsuits. The sands ranged in hue from red to golden and ochre and brown.

DUNE MOVIE WEBSITE

Back when Morgan was a fashion designer for Barneys, he designed a gauze line and recalled how gauze shifts in a similar fashion to sand. He applied this technique to the stillsuits where he dyed the gauze sand-like colors like salmon, dark rust, and pale-gray-beige—which became the palette.

Paul Atreides

Paul undergoes a change in wardrobe as he moves from Caladan to Arrakis. As mentioned above, the regal Attriedes family dresses in elegant uniforms.

DUNE MOVIE WEBSITE

Paul’s wardrobe changes along with his misfortune. The films of Sir David Lean, most notably Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago, inspired West. His Zhivago-influenced jacket had neither buttons nor zippers as West doesn’t believe that they will be a feature of the future. Instead, rare-earth metals and magnets were used to close Paul’s collar.

DUNE MOVIE WEBSITE

Upon his escape into the desert, Paul’s look transforms into Lawrence, trading in his fanciful garb for survival gear akin to the Fremen.

Lady Jessica

As the mother of Paul, a member of the Bene Gesserit, and a concubine of Duke Leto, Lady Jessica delicately balances both power and vulnerability. In the beginning, she’s not quite royalty but she still enjoys the luxury of decorated masks, veils paired with an enigmatic eye pendant, and bejeweled finery.

DUNE MOVIE WEBSITE

She also wore a black gown that Ferguson compared to a black sock, and with its hood up, it allowed her to remain undetectable when standing in the shadows.

“Jessica gets to be in the big room, but there are no other women there. Still, she has power and can kill anyone with a snap of her fingertips.” -Rebecca Ferguson, Vogue

Duke Leto Atreides

Just as mentioned with Paul’s attire, Duke Leto Atreides radiates royalty, inspired by the Romanovs, and more specifically Czar Nikolas II for his dress uniform.

DUNE MOVIE WEBSITE

For Leto’s armor, West and Morgan brought a sci-fi approach to medieval armor. Their interpretation appeared like the plated steel of a knight’s armor but shaped for space and engineered with futuristic materials.

Baron Vladimir Harkonnen

If the Baron (Stellan Skarsgård) looks familiar, it’s not just your mind playing tricks on you. When West first considered the Baron, she was struck by Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando) in Apocalypse Now.

STILL FROM DUNE, 2021

“It’s all derivative, right? We are affected by what we’ve seen in our lives, expressed in our lives, and can bring all that forward. Whether consciously or subconsciously, you bring it forward.” -Bob Morgan, SlashFilm

Gaius Helen Mohiam

Gaius Helen Mohiam (Charlotte Rampling) is the Reverend Mother of the Bene Gesserit and holds authority over Lady Jessica and Paul Atreides. For her garments, West and Morgan referred to images of nuns cloaked in black from top to bottom.

STILL FROM DUNE, 2021

Mohiam’s face is only slightly visible through a mesh net-looking veil. “Denis started with a drawing or an illustration we saw,” recalls Morgan, “And then, how do we make this into a costume and then something you could peel away and see what’s underneath a little bit? Not revealing it totally, because it’s almost like looking at someone in a confessional in a way, right? There’s a barrier there with a door open only a little bit.”

●Locations○

The production of Dune spanned a few countries from the stages of Origo Studios in Budapest, setting up shop at the Wadi Rum rocky valleys in Jordan and Abu Dhabi to the Stadlandet peninsula in Norway. Each of these places helped represent the planets of Dune.

SET PHOTO: GREIG FRASER

Cinematographer Greig Fraser has extensive experience with virtual sets and helped perfect the volume for the Disney+ series The Mandalorian. However, rather than rely on the volume or greenscreens, Villeneuve preferred the authenticity of shooting on location in real environments like deserts to benefit from real lighting. (Though, the volume may not be ruled out for Dune: Part 2.)

“When I think about volume work it’s not all or nothing,” Fraser said in an interview with IBC. “Using the volume is most effective when it’s used for the very best things and you use the real world for other scenarios. For the next Dune who knows maybe if we can mix and match shooting volume with real-world scenarios, the whole system becomes even more powerful.”

Learn more about the volume and how it’s an innovation that will increase cinematic possibilities.

PHOTO CREDIT: CHIABELLA JAMES

Shooting On Location

They filmed all of the rock desert scenes in Jordan and the desert dune scenes in Abu Dhabi. Authenticity breeds believability. That’s why the dry air of the desert that the actors had to breathe also added to the value of their performance, according to Walker. The sets depicting the palace structures at Origo Studios were so vast that you could feel “the weight of the oppression.”

Perhaps it was Villeneuve himself who had the best time in the desert, who worked tirelessly with various units every single day. He told postPerspective:

“The desert is physically very tough but I would not complain because it’s paradise, and we had perfect conditions for shooting. I dreamed of having a very harsh, white sky with strong winds, and we got exactly that for a whole month when we were in Jordan.”

PHOTO CREDIT: CHIABELLA JAMES

Though, the entire shoot wasn’t sunshine and ornithopters. Back in Budapest, production contended with the rain while filming outside. As Villeneuve would later note, “the one thing you can’t have in Arrakis is water!” so the team had to secure even more stage space to overcome the weather conditions.

●Production Design○

Production Designer Patrice Vermette admires science fiction for its ability to serve as a mirror to our own world.

“I think Dune is the perfect book for that matter as it talks about colonialism, imposing ourselves on other cultures, our exploitation of natural resources, and the way we’ve been treating the planet and each other. When you see Giedi Prime [The home planet of the Harkonnens] it’s where we’re heading.” -Patrice Vermette, Science Focus

Conceptualizing Worlds

Vermette began his process by researching the worlds online and collecting images and illustrations from books, then sharing them with Villeneuve. In turn, Villeneuve shared Richard Avedon photography with Vermette, as well as photos of bunkers from WWII, ziggurat architecture from Mesopotamia, and images of the war in Afghanistan. This ignited a conversation between the duo about how colonialism forces itself upon the landscape. Vermette recalled that this led him down a rabbit hole to concept artists like Nicolas Moulin and of Super Studio.

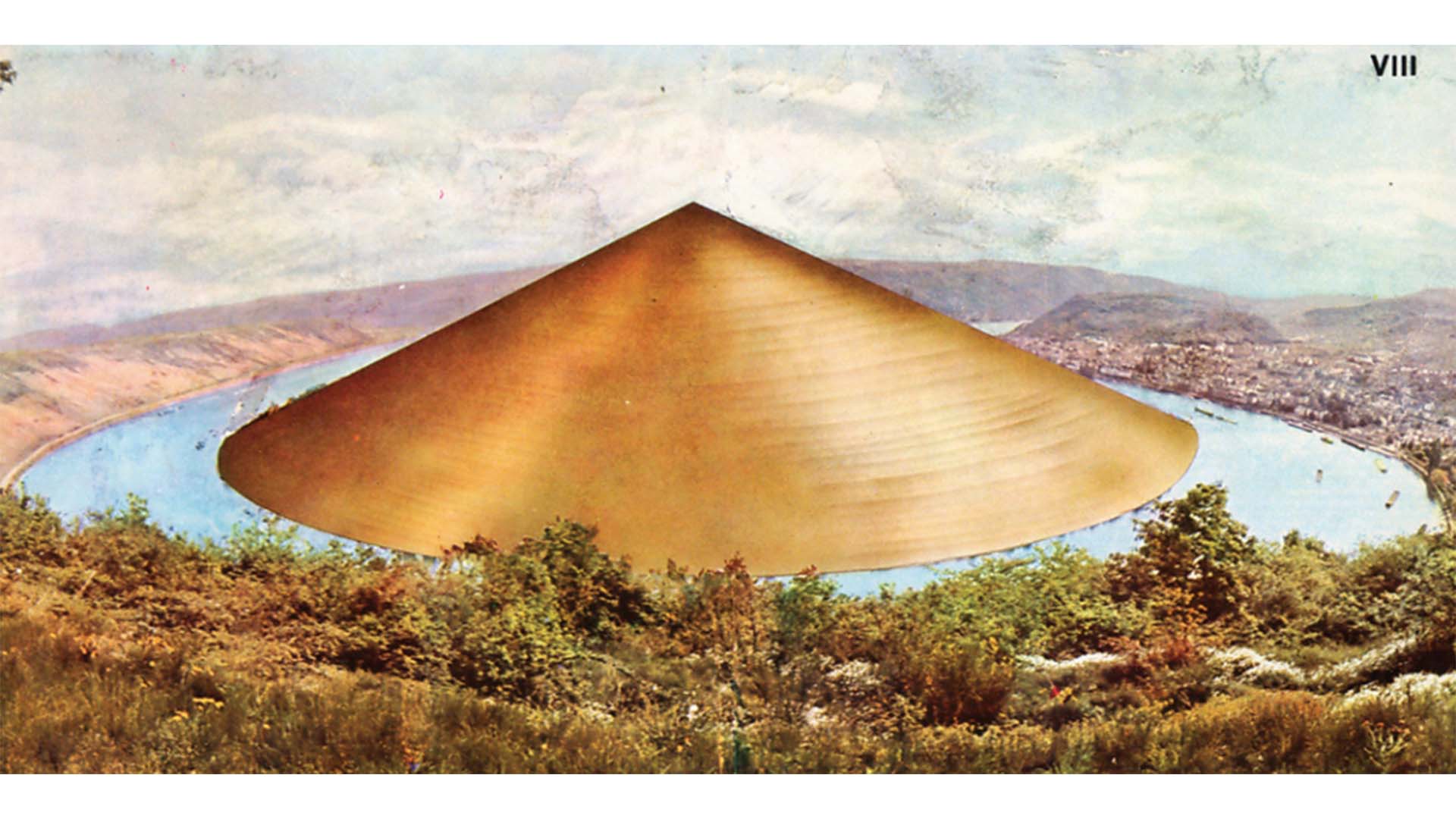

Nicolas Moulin Wenluderwind Series

Radical architectural firm Superstudio

Radical architectural firm Superstudio

“I think that imagery resonated in what we wanted to create in the world of Dune, said Vermette, “the sense of scale, and a sense of imposing yourself on a place, and the idea that these structures can show the power of a nation. That was very important for us.”

Upon discovering the right tone, they sketched their ideas out and brought in concept artists who worked on their mood boards. This is where they hatched out the scale of the architecture and conveyed how the light would play. They started with a wide scope before working their way into the finer details of each world.

According to Vermette, once Villeneuve marries an idea, he never turns back. This allows the artists around him to dig deeper into their designs without the fear of reinventing them into something entirely new.

Collaborating with Other Departments

Together with Villeneuve, Paul Lambert, and Fraser, Vermette worked together to conceptualize the world. They built sets using the basic technique of wrapping real materials and colors that represented the real stone to scaffolding.

SET PHOTO: GREIG FRASER

The production design was achieved also together with the art department and set extensions were created by Lambert and the VFX team. The lighting would suffer if they had decided to only build 12 feet up and used blue or greenscreen for the other 18 feet. Instead, they lit the scene correctly and the VFX extensions molded to match the lighting setup.

Caladan

Caladan is a lush planet with bountiful oceans and agriculture so its economy centers around rice, wine, and fisheries. In addition to its economy, its architecture is inspired by medieval castles but also infused with Mayan, Aztec, and Japanese designs. In the design of its castles is artwork that tells a story about the ruling family’s history.

Training room in Caladan. COURTESY OF WARNER BROS PICTURES

Vermette and Villeneuve are both French Canadian and decided that they would base Caladan’s weather on Canada in autumn. “It’s not too hot, not too cold.”

Arrakis

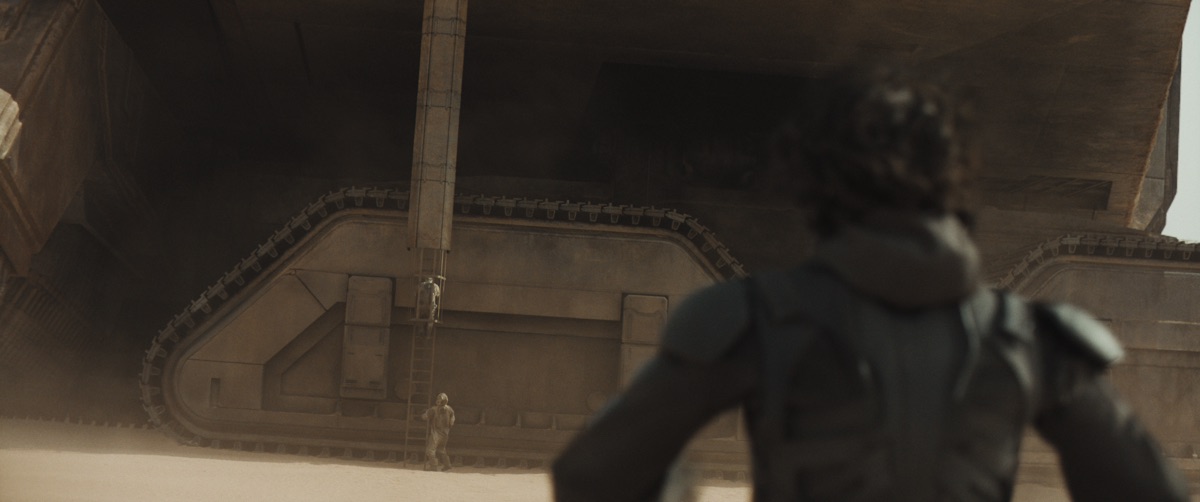

When first deciding on the look of Arrakeen, the primary city on Arrakis, Vermette turned to images of the brutalist architecture from both Brazilian and the ex-Soviet bloc. Arrakeen was most likely erected after the discovery of spice melange by the colonial forces. Its architecture conveys its power and sovereignty over the natural world.

STILL FROM DUNE, 2021

“Scale also helps Paul’s visual journey as something more comforting, nostalgic, romantic on Caladan, to the harsh reality of Arrakis. It’s bigger than anything he could’ve imagined. So that’s the process of the design.” -Patrice Vermette Dune News Net

From there, Vermette put on his city planner hat and considered the natural environment and the variables at play to subsist with intense heat, violent wind speeds of up to 530mph, and an enormous Lovecraftian worm.

A city on Arrakis would have to be constructed in a ‘Goldilocks’ zone that would protect from all three of the aforementioned elements. The solution was a protective mountain bowl with impenetrable rocks and angular-shaped structures so the wind would brush off of them rather than through them.

The Palace at Arrakeen

The Palace at Arrakeen stands as the largest known structure in the whole universe. Therefore, Vermette let his imagination run wild. While, simultaneously, he knew that there were no green screens and they dealt with limitations to space due to budget. They developed tricks such as moving walls to create different spaces and constructed areas beyond 24 feet out of fabric.

Arrakeen concept art

To clarify, sets were built using fabric on frames for city structures, painting them the average color of the sets. This technique was very useful when it came to lighting as they could represent what areas were concept so the VFX could go in and add the right texture. Plus, there was no green light contamination to deal with. The benefits of this kind of lighting environment only helped the VFX to better integrate their work.

To make the world feel old and lived in, Vermette went out of his way to crack walls because “that’s what happens in construction.” In addition to this, you could feel the ash and moisture from the moss growing on the structures.

The Imperial Nexus Laboratory

The main room of the Imperial Nexus Laboratory was Vermette’s greatest challenge. There were alot of factors at play that needed to go right for this location.

Main room of Imperial Ecological Testing Station

It was shot on a sound stage that was only 65 feet high. They calculated the size that their ceiling would need to be with false perspective using computer models and the sun’s orientation in the sky. This, in turn, would create the shadows necessary that they needed to stretch across the floor.

The roof was constructed with (you guessed it!) fabric so they needed a day with no wind and 10-11 days without rain to ensure the sand was sufficiently dry. Agricultural equipment was used to turn the sand to keep it dry, as well. What made this location even a bigger challenge was the location of the sound stage in regard to the sun’s path. That meant that they could only film between 10:45 A.M. and 11:20 A.M.

The Imperial Lab was also rich in Fremen history. Reasoning that before the discovery of spice melange, Vermette concluded that the emperor would have hired local Fremen to build the walls. And like the ancient Egyptians, they wrote their language on the walls and told their story. It’s how they keep their culture alive while suffering exploitation at the hands of colonialism.

PHOTO CREDIT: CHIABELLA JAMES

The mural of the sandworm is the first visualization of the iconic creature in the film and depicts it essentially as a deity. Also in the mural is a harvester that reveals that this exploitation has been happening for a very long time.

The Baron’s Environment

As an evil goth-inspired Harkonnen, the Baron’s lair was dark and shadowy with tall ceilings like a cathedral.

DUNE MOVIE WEBSITE

The Baron is reminiscent of an evil priest so to add to the intensity of his environment, Vermette implemented enormous ribs as you would see in the inside of a whale.

●Cinematography○

The cinematography of Dune captured a planet of interstellar proportions while also zeroing in on the plight of the Atreides family and Paul’s journey as the Chosen One. Fraser was one of the best DPs for the job, lensing titles like Foxcatcher, Rogue One, and episodes of The Mandalorian.

Fraser once said, “You should have a POV on that lighting; it should be from your experience… so before you even pick up a camera, you need to develop an aesthetic and an opinion.”

PHOTO CREDIT: CHIABELLA JAMES

Fraser’s cinematic eye focused on a story that relied on sensory images that were carefully selected by editor Joe Walker. In an epic, you’re typically enthralled by large, extravagant shots, but with Dune, there are soft, unspoken moments that speak volumes.

Walker’s personal favorite moment involves Lady Jessica awaiting as the bull is packed on Caladan before embarking to Arrakis, and Leto’s hand falls into frame and reassures her. We all know the feeling of a hand clasping the back of your neck. At other times, it might be a hand gliding through the water or a foot touching sand for the first time. The visual storytelling had to allude to this greater world surrounding Paul, just as much as it had to do with Paul himself.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT

“To be as good as the artwork.”

While filming Blade Runner 2049, Villeneuve learned a few tough lessons. One in particular from the master cinematographer Roger Deakins.

“I’ll always remember Roger Deakins telling me, ‘Your artwork needs to be dead-on, otherwise it’ll be chaos in post.’ He was so right, and I learned that the hard way. So after that, I had to fight to make sure we brought it all back to the original artwork.”

Fortunately, Fraser was on the same page as Villeneuve and even commented that he wanted to try “to be as good as the artwork.” This was music to the director’s ears. This time for Dune, Villeneuve was certain to communicate such details so everyone was on the same page.

“When you look at the artwork for this and then the final movie, it’s the same exact look. I’m very proud of the look and Greig’s work. Greig and Dave [Cole] completely embraced the vision that myself and Patrice Vermette originally did on paper, and it turned out just the way I dreamed.” -Denis Villeneuve, postPerspective

Shooting for IMAX

In the early stages of Dune, Villeneuve expressed to Fraser that he would like to shoot in an unconventional 4:3 that is closer to television. However, 4:3 is also better for IMAX (1.43: 1) and works wonderfully for articulating Paul’s hero journey and his proximity to the spice.

DNEG Visual Effects Supervisor Brian Connor told ProVideo Coalition that “everything was shot for IMAX,” meaning if you see the film in 2.39 you’re missing parts of the top and bottom frame. Since IMAX is more of a square format, there’s more room for imagery on the screen. Connor and his team added mega frames for select shots that Villeneuve and Fraser wanted for IMAX resolution. This added to their rendering process, including a 2.39 crop plus the IMAX render.

“We weren’t just chopping the 2.39 out of an IMAX frame.” -Brian Connor, ProVideo Coalition

The Fraser Method

To still achieve that “analog quality,” according to Fraser, they performed a new technique that we might as well dub the “Fraser Method.” With Fraser’s newfangled technique, the digital negative was scanned out to film and sent to FotoKem to be rescanned back to digital.

Master Colorist David Cole explains, “It’s not like a printable negative, it’s special like a data-negative. Then, we scan that back, match it back.”

The Fraser Method

- Shoot Digitally

- Final Grade Before Hitting Neg

- Output to Film

- Scan Back

- Grade the Scan (Final Creative Tweaks)

“We all remember what it was like to work on film—all the bad things and problems with the lab—but also all the great things—the beautiful, emotional images. I still have a very strong love of an emulsion, and the big question is, ‘Where does emulsion come in the process?’ Does it come by acquiring image, or afterwards? I’m sure there are very film-centric filmmakers out there who’ll have my head on a platter for saying this, but I felt that for this film, putting an emulsion in the process after the fact was the right approach.

“You get that analog film look just like in the old days when you could sculpt a look depending on what stock you went with—Kodak, Fuji, etc. Whether you underexposed and overdeveloped it or overexposed and underdeveloped it, or flashed the film, you had all these opportunities to give it a certain feel and look.” -Greig Fraser, postPerspective

When the industry adapted to digital over celluloid, filmmakers lost many options of film stock. However, with the Fraser Method, you’re free to choose with your choice of digital camera, then choose the stock you wish to print, ranging from negative stocks, print stocks, 35mm, and 65mm. You can still dream and experiment and find a concoction that is entirely your own.

●Camera & Lenses○

Early on in pre-production, Fraser and Villeneuve thought about using film since they were filming an epic. To help determine Dune’s visual language, they performed tests in the Californian desert near the Salton Sea. It was close enough looking to Abu Dhabi, according to Fraser. He likes to shoot tests and then sit with the director to gauge their reaction.

Cinematographer Greig Fraser on the set of Dune

During tests, they shot everything from 35mm film to large-format ARRI Alexa 65 and IMAX. They also ran the spectrum on anamorphic and spherical. But while reviewing the tests in Playa Vista, Villeneuve didn’t feel film was the right look for Dune. It was too nostalgic. Plus, they wouldn’t have access to dailies while shooting on location. The clarity that comes with digital capture was better but still wasn’t “organic enough” for Fraser’s tastes. They needed something that was more in-between.

The Best of Both Worlds

Their camera of choice was the ARRI Alexa LF 4K and Mini with Panavision H-series and the Ultra Vista anamorphic lenses that Fraser had built with Panavision for The Mandalorian.

“We could get the film characteristics that we liked from the 15-perf because grain is not really an issue at that scale because it’s so big,” says Cole. “So, the whole film-out process on this film wasn’t about grain. It was about everything else that film brings to the table. So you know, slight flicker and inter-layer interactions and slight blur and hallation of the highlights. So we found that the shooting on the LF gave us all the flexibility of digital acquisition, and especially on locations like that, but all of the great characteristics of film.”

During the first part of the movie when the Atreides are still home at Caladan, there’s a more formal, traditional look. Then, when the plot moves to Arrakis, the composition becomes more unstable. For this part in the desert, they shot a handheld style in IMAX.

●Color & Texture○

One of the most notable takeaways from Dune is its muted color palette. The dryness of the environment and its scorching sun presumably bake away all colors. The climate of Arrakis is brutal and quickly obliterates and conception of romanticism in the desert. The color and texture scream that this is a dangerous place where you likely won’t survive.

“I wanted nature to be powerful and abrasive,” Villeneuve professes, “not beautiful…. At the start, the look of the desert is more mesmerizing to Paul, but the more he gets inside it the more dangerous it becomes.”

Lookup Tables

The look of Dune was purposefully desaturated where there were no colorful, vibrant rocks and sand nor bright blue skies. In fact, Cole and FotoKem designed a lookup table (LUT) to emulate a true skip bleach negative while also reducing the blue sky while and softening the toe and shoulder of the curve. Utilizing another LUT provided by Fraser, FotoKem co-created its LUT by adjusting the tonal characteristics of the shadows and highlights to soften the contrast.

Master Colorist David Cole works on Dune

“[For] Giedi Prime or Caladan, we wanted a more traditional filmic LUT,” Cole tells Filmmakers Academy. “But we wanted to really have air in the shadows, so we never wanted anything pitch black, we wanted to be able to read down in there. We wanted soft blacks. So, we manipulated a more traditional—I’ll use that loosely—but a traditional film LUT to have those softer tones down the bottom end.

“And then on Arrakis, when you’re outside, I will say 90% of when you’re outside is using this alternate LUT, which was emulating skip bleach. And we did a true emulation because we actually took the footage, put it through skip bleach at the lab—because at FotoKem we’re a lab, so we can do all this photochemical treatment—and then we matched it back so that we had a true skip bleach emulation of the film stocks that have gone through that process, and then we soften the contrast a little bit because we didn’t want it too harsh, and we allowed the bottom to have air in it, and then we manipulated the top end so that we didn’t get a lot of saturation.”

Fraser worked closely with his DIT Dan Carling on set to ensure that they gathered the right images and graded them correctly.

Digital Intermediate (DI)

Master Colorist David Cole of FotoKem was essential to helping the film achieve its look, and he delivered precision to bring out features of light, contrast, and atmosphere.

DUNE MOVIE WEBSITE

Fraser constructed a color bible with Cole on Blackmagic’s DaVinci Resolve. Before he was called to his next film, they strung together a DP cut of every scene with the correct color grade. This allowed the VFX team to have a reference to work off of.

Connor notes that when working with such a desaturated look, the details and textures need to be that much more precise. It took a lot of time to get scenes right, like the Atreides arrival on Arrakis due to its sheer scope.

“To me, the grade is as much Denis’ and the colorist’s and the production designer’s. It’s a communal effort. The grade is the movie’s grade, and I trust Denis’ and Dave’s opinions implicitly.” -Greig Fraser, postPerspective

Villeneuve worked closely with Cole to dial in the coloring process to meet his specific desires.

Want to learn how to color grade like the masters? Go All Access with Filmmakers Academy to receive courses from Master Colorist David Cole as well as all of our other educational filmmaking content!

●Lighting○

The use of light in Dune may seem unorthodox to some but it falls entirely in line with its visionary. As Villeneuve had previously mentioned, he wasn’t looking for a look that was nostalgic or romantic. So, they avoided filming sunrise and sunset scenes to maintain their logic. Not only did they shoot on location, but Villeneuve wanted to also avoid artificial light where he could.

The lighting in science fiction films is often overdone,” says Connor, “where the actors are glowing like “there’s a supernova happening behind them” but Dune doesn’t “suffer from those things.” They originally set up a virtual lighting rig built for production, but it was for a scene of the movie that didn’t make the final cut. Otherwise, there was no other virtual lighting.

Day Exteriors

This was a story with a world that dealt an unrelenting scorching to its desert environment with a bleached sun and bone-dry atmosphere. Therefore, outside the days were white-hot and desaturated so the audience, through visual osmosis, felt as parched as the characters on the screen. While filming in Abu Dhabi and Jordan, Fraser backlit the actors to avoid panda eyes—dark eye sockets.

In Budapest, Villeneuve wanted to keep with his theme of using natural light. So, they erected tents outside between the stages and built their set pieces to achieve the right amount of shadows and sunlight.

Night Exteriors

To maintain using as little artificial light as possible, Villeneuve delivered another look audiences aren’t typically used to seeing. He chose to use no artificial light for night exteriors.

Before the digital age, it never before was possible. They shot beneath the shadows right before sunrise or sunset where they had only 45 minutes of usable light free of shadows.

Day Interiors

While they bathed the outside in dry heat, the interior is cool and dark… and without windows. This could present a problem as there is no way for sunlight to shine in. However, in the Arrakis fortress that can supposedly withstand both war and heat, there’s an intricate series of light wells, conceived by Villeneuve and Vermette. Rather than dealing with direct sunlight, the light wells are a “byproduct of bounce light through the shaft,” Fraser explains in Variety.

“It’s not hard for the sun to look super harsh, so trying to find that balance and stay cinematic was still a challenge to ensure the shots weren’t badly lit.”-Greig Fraser, Variety

●The Edit○

There’s a rhythm to Dune that’s paced very eloquently and it’s very much in line with its editor Joe Walker’s musical background. The editor of Sicario and Blade Runner 2049 injects musicality into his editing that’s not always auditory, but rather a combination of movements.

DUNE MOVIE WEBSITE

“There’s the rhythm of a shot itself, of the composition, and then there’s the rhythm of the speed of that shot, explains Walker. Then, there is a rhythm of the performance within it. And then, there’s the sound effect that goes with it. And then, Hans’ music that is on top of it. I have tentacles going out into all these wonderful departments and together we’re building a rhythm.”

It’s no surprise that Villeneuve works very closely with Walker, and has done so for years. Together, they dissect the plot, the momentum of the story, the small details and moments that deliver an interesting payoff down the road.

Editing for IMAX

They started editing for 1:43 since the majority of desert scenes for Arrakis were shot for IMAX. At first, Walker was concerned about working with the two aspect sizes and if it would be “noticeable or damaging.” However, his concerns were quelled when he realized the amazing and free capacity that IMAX delivers.

In conversations with Christopher Nolan, Villeneuve was reassured that they could drift between 2:39 and 1:43 on the IMAX screen, and since it’s so large, it’s not a jarring change. They started cutting the film at 1:43 until they felt comfortable, and then they switched to cutting at 2:39.

PROVIDEO COALITION

“It’s very important to look at that stuff and to see for VFX that it is considerably more plate for them to have to figure out, if there’s a bit of vegetation on the floor that can’t be there on Arrakis, then that might be on the foot, and you don’t see it if you’re cropping. I think it was advisable to them to look at the full aspect ratio as we did our first cuts, but after a while, we zoned in on the 2:39, and it felt like a more comfortable, less distracting viewing experience for most people when we’re getting, about to show to the producers and things like that, we flipped over to the 2:39.” -Joe Walker, frame.io

Dream Visions

The hypnotic dream visions were especially mesmerizing. It took a long time to convey Paul’s dreams and his inner self. In fact, it took until the day before the drives were to be turned in before Walker finished finessing it.

The concept for the vision sequences came from how the camera chip responded to the sunlight in a way that was unique to that specific chip. When Villeneuve saw how it looked, he asked the camera team to film directly into the sunlight while slowly moving the camera. This produced hours of material for Walker to choose from.

“The idea was it feels a little bit like when you’re a 14-year-old kid dreaming in the summer and your eyes are shut. It’s a sense of almost seeing your eyelashes at one point with these beautiful striations of light.” -Joe Walker, frame.io

Fight Sequences

The fight sequences came together much easier than the dream visions. In fact, the first edit was the one that made it to the final product. This follows Villeneuve’s process of not messing with what’s already working. He invests that time into the components that still require his attention.

PHOTO CREDIT: CHIABELLA JAMES

A Light Touch

Walker edits in a way where you don’t feel his hand guiding you along. He’s not interested in being overly showy or moving the plot in a way where it feels manipulated.

An example of this is in the scene where Stilgar (Javiar Bardem) first meets Duke Leto and they’re accompanied by Gurney Halleck (Josh Brolin), Thufir Hawat (Stephen McKinley Henderson), Duncan Idaho (Jason Momoa), and Paul Atreides. Stilgar walks in the room past numerous guards, sizes them up, and spits on the table, then everyone rushes to attack him.

The room is full of heavyweights who are all delivering something amazing. As an editor, you’re split between so many performances. However, Walker chose to stick to his guns and he didn’t break the shot with Stilgar in a medium to medium-wide shot taking in the room before he clears his throat and spits.

“You could have cut that differently. You could have cut it to Paul, looking at him and appreciating Stilgar. There’s some sense of mutual recognition there. You could look at Thufir Hawat for his anxiety that this meeting did not start well. There are a dozen reasons why you might go to another actor for that moment, but I’d just like not to get in the way of the performance, which I thought was superb.” -Joe Walker, SlashFilm

Editing Dialogue

Recalling his musical rhythm, Walker advises that there’s also a natural rhythm to dialogue that you can follow. A way to check your pacing is to turn the volume off and watch the shots play out without audio. That’s when you become more aware of the actors’ eyes.

In an interview with Steve Hullfish, Walker provides an example of how he edits dialogue: “The easiest cut to make in dialogue terms is, ‘Why did the chicken cross the road?’ [Snaps] ‘To get to the other side.’ [Snaps] You know that there’s a rhythm that’s built into the rhythm of those words that’s driving the cut point. If you are aware of that simple trait, then you’ve just disassembled all of my dialogue editing.”

The Close-Up

The close-up is key to how Walker observes and edits a scene. He sees the main source as the close-up because there’s an intensity that shines above all the other shots. When observing dailies, Walker jumps to the moment (that we refer to as our keyframe) in the scene that requires the close-up and then builds the other shots around it. Depending on the shot, he’ll sometimes even cut backward.

Editing Before the VFX

Before going through the costly stage that involves your VFX team, the editor must set the space and timing within the scene. Walker does this by adding visual placeholders that articulate the movement of the future effect.

One such placeholder is a video texted to Walker of Villeneuve’s hand moving a box of matches with his hand to show how long a shot should be. Then, Walker literally took that video and put it into the edit to convey that same message to the VFX team.

In a similar fashion, during the scene with the hunter-seeker (a deadly bug) that emerges out of the headboard in an attempt to attack a reading Paul, Walker’s assistant Mary’s voice was used to serve as the fly. Then, with the empty plates of the room, Walker hatched an idea.

“I ended up using some texts with the title tool, says Walker, “and I had the word ‘hunter-seeker’ moving, and if I may say [laughs] I outdid myself by using perspective, which I’d never done with the title tool before. Anyway, every shot had the word ‘hunter-seeker’ going past very slowly in the foreground.”

Patrick Heinen and Javier Marcheselli were able to take his ‘hunter-seeker’ on the screen and change it into the bug from there.

The ‘Walker Trick’

Walker applies a particular technique in all of his films, but for Dune he took it even a step further.

The trick is simple and involves a cut. Basically, in the first shot, you have someone looking very intently and then you cut away to something else. That way, it appears that they’re thinking about that second image.

“With that simple trick, I’ve carved out a little niche in Hollywood,” laughs Walker.

For Dune, the motivation of the cutaways evolved and seeded itself within the narrative for a sumptuous payoff. Such payoffs include the feathering in of the crysknife and the foreshadowing of Chani (Zendaya).

●VFX○

Hollywood rarely makes the kind of epics it once did like Apocalypse Now or even Braveheart, where CG wasn’t the main feature of its production. Dune was an emergence between old and new with well over 2,000 VFX shots.

DUNE MOVIE WEBSITE

Villeneuve started working with VFX and his post-production team early in pre-production to help conceptualize the design and build. They determined the aspects of set that were real and set extensions, then previz’ed all of the vehicles and creatures so they could plan the plates needed for visual effects.

“There’s been a lot of talk about how much we did in-camera, but the truth is, everything we did in-camera had some sort of VFX work done—a fix or addition and enhancement and so on.” -Denis Villeneuve, postPerspective

COURTESY OF DNEG © 2021 LEGENDARY AND WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT

COURTESY OF DNEG © 2021 LEGENDARY AND WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT

When COVID struck, the filmmakers were set to conduct their post-operations in Los Angeles at Legendary’s facility. They pivoted by moving all of the screens and communications equipment to Villeneuve’s home in Montreal where he directed them remotely.

Blue & Green Screens

Chroma key compositing changed the industry by doing things like transporting actors to different worlds and creating the movie magic we all know and love.

Green and blue screen technology have become a modern-day feature of filmmaking but lighting can be challenging and the process itself is distracting for actors staying in character.

Sand Screens

Production VFX Supervisor Paul Lambert and his team chose to use ‘Sand Screen’ or a color that closely matches the environment by using a simple trick. They began by choosing the best type of blue screen for their key, brought it into NUKE, and then they inverted and keyed it to get their sand color.

“We have these 40 x’s, and we’d move these massive sand screens into place where we needed them, like if we had some close-up footage or coverage that we needed to do. And one of the interesting things that I found was no one cared when I would ask to move the sand screen around, not like they would a blue screen.” -Brian Connor, ProVideo Coalition

By pulling the key, you’re not stuck with blue, green, or red. Instead, you can choose what solid color works best for separating the background from the foreground. Then, like in the case of the sand screen, they would invert the image for the sand screen to shift back to blue with both your edges and extraction.

“The density of it wasn’t perfect for the core,” says Connor, “but I really don’t care about that as much. ‘Cause, we can order roto pretty easily, right? But what we can’t do is roto hair and all of the little wonderful, subtle detail that you have in the edges. So that’s where the sand screen and that technique comes in.”

Vehicles

The team constructed the vehicles, except the spice harvester, onto a track in real-life proportions. Every flying sequence was the product of VFX. So, while the ornithopter bodies were real, there obviously is no aircraft that moves quite like it.

Ornithopters fly much more like a dragonfly than they do a helicopter, so that’s where the CG team had to come in. They used helicopters as a visual reference for light, reflection, and color, then they flew them up off the ground and then landed them in Montreal.

PHOTO CREDIT: CHIABELLA JAMES

“They landed a helicopter first and we studied that kind of roll and all of the particulate dust, and we didn’t use it as an element—because we couldn’t. If we could, we’d always use stuff that was real practical effects on set, and we would augment it where we had to and we’d learn and just watch what that did and use it as reference.” -Brian Connor, ProVideo Coalition

The Crash

For the ornithopter crash, it was the stylistic choice of the director. After the aircraft loses a wing, it would most likely go down hard and fast. However, Villeneuve had done some previs and had a specific vision in mind. The VFX team would send Villeneuve something and then he would advise them from there.

PHOTO CREDIT: CHIABELLA JAMES

The VFX team also mastered the water effect when the Atreides’ flagship was departing Caladan. It was a long and arduous process. They used references that Lambert found of ice sheets breaking off icebergs.

PROVIDEO COALITION

“We studied ad nauseum, just to make sure that we had that scale right. Because it’s so hard to get that right. The first ones out of the gate are pretty fast, but then once you start getting into the minutiae, it just takes time to do. And luckily on this show, we had the time we needed to make it look great.” -Brian Connor, ProVideo Coalition

Sandstorms and Sandworms!

One may be convinced that the sandstorm scene was shot while on location in Abu Dhabi or Jordan—but then, one would be wrong. Since the sandstorm was actually filmed in Montreal (you read that right, Canada!), the VFX team had to turn to references of sandstorms in the Sahara desert and even footage of sand devouring Denver.

COURTESY OF DNEG © 2021 LEGENDARY AND WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT

COURTESY OF DNEG © 2021 LEGENDARY AND WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT

They worked to construct a massive scale that could best represent Arrakis and its titanic sandworms. The team started by modeling their desert off of our Earthly desert-scapes and took note of the tips of dunes. In order to inject the earth-shaking power of the sandworms both above and below the surface, they devised a special process to simulate the sand effects. (A portion of this involves practical effects, and therefore, can be found below.) The rendering of all of their effects with big Houdini simulations was difficult to render, even with their extensive number of processors, and taking up copious amounts of disk space.

Force Fields

The force fields were an aesthetically satisfying effect in a futuristic tale with an otherwise modest conception of sci-fi gadgetry.

Everyone had their own personal force fields that illuminate blue when struck and flash red when attacked with, say, a crysknife, allowing them to puncture that shield. They also used this same general concept during the attack on the spaceport.

The effect of turning the shields on and off was the product of a comp gag. “You use before and after frames and you blend them together in an interesting way to achieve that force field look,” explains Connor.

●Practicals○

While one side of the equation for the look of Dune was accomplished via VFX, the film’s practicals were central to its scorching realism. These effects spanned high-impact demolition down to the whisps of sand cast at actors by crewmembers.

There were lots of explosions to capture courtesy of SFX Supervisor Gerd Nefzer and his team. Later, in VFX, Connor and his posse then copied the explosions “down to the pixel.”

“There were just a lot of special effects in there as well to help us marry in everything that we were adding to this.” -Brian Connor, ProVideo Coalition

Lambert and his crew extensively documented every aspect of where the lights were, what lenses were used, and used LiDAR in case they need to build sets or add a scene later. Overall, the data collected informed them of their light quality and other prevalent information.

Sand Effects

Sand is synonymous with Dune and its vast deserts of… well, dunes. While much of the sand was from real deserts and some on the backlots of Budapest or Montreal, the manipulation of the sand was also authentic. For the most part.

The concept for the sandworms was at least in part inspired by the shark in Jaws. You don’t see the sandworm right away, you hear them and feel their immensity underneath your feet. Just like how in a good scary movie you don’t see much of the monster. The idea of the monster and what the imagination can cook up is much scarier than any visual.

DUNE MOVIE WEBSITE

“I think really they’re saving a lot of [the sandworm] for the second part which, now that we kind of have an approach to it… Obviously like anything else, the first one’s the hard one, figuring it out, but the next time it comes along, you have some efficiencies that you can use to then leverage versus making it up.” -Brian Connor, ProVideo Coalition

To manipulate the sand underfoot, they engineered a large version of a shaker machine (equipment typically used for weight loss). They buried the machine in the sand to generate the shockwaves that are presumably coming from a sandworm.

“We found that when you have a specific frequency then people start to sink,” describes Connor, “So when you see those scenes, that actually is just real sand tuned to a specific frequency where it starts to sink.”

Hologram

Paul uses the hologram as an educational tool. In the scene where he watches a holographic scene and hunter-seekers enter the room to attack him. Paul hides in a 3D digital projection of a bush to avoid detection.

Lambert’s VFX team could have expensively handled the scene by making the lasers interact digitally with a digital double of Chalamet. An interactive alternative was conceived on set by DNEG to interactively track Paul.

STILL FROM DUNE FILM

“Timothée Chalamet had markers on him, and the location was rigged up as a MoCap set, with readers up on all the rigs, so we knew where he was going to be as he played through the shot,” explains Lambert. “The holographic model for the bush had been signed off by Denis, so we sliced the bush into hundreds of thin sheets of light. We’d project just one of those slices onto Chalamet, depending on where he was. The system was set so as he moved forward, the slice would change to the next slice of the bush. As he moved around, it looked like he was penetrating into the bushes. And because we had this tactile interaction from the actor to the lighting, this became a real live part of the scene.”

To complete the effect, Wylie&Co was tasked with adding more digital bush around Chalamet to better obscure him from his pursuers.

DUNE MOVIE WEBSITE

To learn more about filmmaking techniques, join Filmmakers Academy’s All Access membership and gain courses and lessons from industry professionals at the top of their game!

Sources:

Filmmakers Academy

Interview with Dune Supervising Digital Colorist (and Filmmakers Academy Mentor) David Cole

Slash Film

- https://www.slashfilm.com/646961/dune-editor-joe-walker-on-finding-the-rhythms-in-editing-narrating-the-sand-walk-guide-interview/?utm_campaign=clip

- https://www.slashfilm.com/660574/dune-production-designer-patrice-vermette-dreams-without-limitations-interview/

- https://www.slashfilm.com/652203/dune-co-costume-designer-bob-morgan-goes-back-in-time-for-the-future-interview/

postPerspective

- https://postperspective.com/dune-director-denis-villeneuve-talks-post-and-vfx/

- https://dunenewsnet.com/2021/11/joe-walker-editing-dune-movie-behind-the-scenes/

- https://postperspective.com/cinematographer-greig-fraser-on-dunes-digital-film-process/

Dune News Net

- https://dunenewsnet.com/2021/11/joe-walker-editing-dune-movie-behind-the-scenes/

- https://dunenewsnet.com/2021/11/production-designer-patrice-vermette-built-worlds-serve-dune-movie-story/

IBC

Variety

- https://variety.com/2021/artisans/news/dune-cinematography-greig-fraser-denis-villeneuve-1235087999/

- https://variety.com/2021/film/news/dune-costumes-1235055713/

ScreenDaily

Deadline

Science Focus

Vogue

VFX Science

ProVideo Coalition