John Williams – The Sound Of Movies

Today we’re going to be taking a quick look at the life and impact of cinema’s most celebrated film composer; John Williams.

Imagine being in a movie theater.

You’ve waited in line to get tickets with all of the couples, the families and the first-time-daters.

You’ve got your trough of popcorn, your bucket of soda and your “sharing size” pack of milk duds and are prepared for the onset of Type 2 diabetes.

You’ve worked your way to Row F, found your seat and set up your base camp.

There’s the raft of previews and trailers. The inevitable buzz when one trailer captures the interests of the audience and they make plans months in advance to go and watch it. The advertisement to turn your cell phone off is greeted with the shining lights of people doing final checks of their facebook/instagram.

Then… the lights dim.. It is absolutely silent.

Put yourself in that moment.

That’s it!

You’re captivated. Your first experience is shaped, not by what you watch, but by what you hear. That is why this series is dedicated to the composers. The people who transport us, musically, to other parts of the world, other worlds entirely, other times, other moments that we may not have ever experienced. It’s hard to imagine Maximus and Proximo’s gladiators battling in the Colosseum without Hans Zimmer’s epic scoring as a backdrop

Jack and Rose standing on the front of the Titanic without the beautiful, sweeping music of James Horner

or even Clint Eastwood staring off for a gunfight with Leo Van Cleef without Ennio Morricone’s haunting musicbox and orchestral subtext.

JAWS

Now, think of a shark… a big shark… one that requires “a bigger boat”… You’re already toying with two repeated notes, played on a cello, getting faster and faster and louder and louder. Jaws. Anyone care to guess how long into the movie, “Jaws”, it took for us to actually see Jaws? That’s right 80 minutes. 80!

John Williams’ soundtrack was so good at conveying the famous fish and building tension that we never caught sight of it until ⅔ the way through the movie! Jaws is the perfect allusion for John Williams’ music – according to a 2005 survey by the American Film Institute, the Jaws theme ranks among the top 10 most memorable scores in movie history. Spielberg was even quoted as saying “John Williams has made our movie more adventurous and gripping than I ever thought possible.”

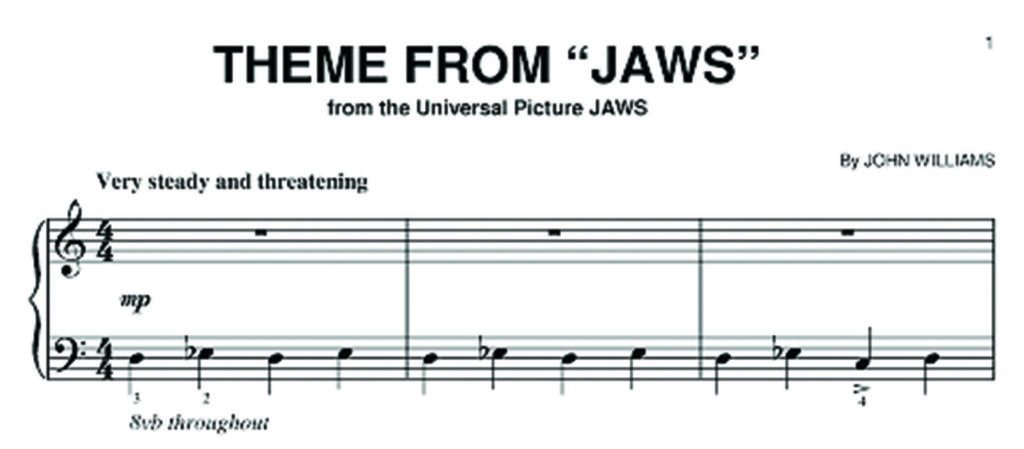

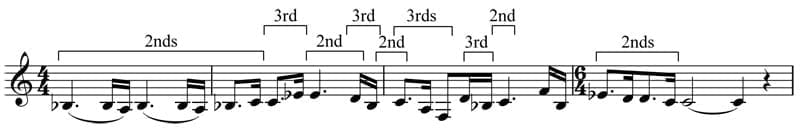

Williams built his soundtrack from the deep, like a shark coming from deep to attack, except this time from deep within the orchestra (low strings, low brass instruments) that were also rhythmic: “so simple, insistent and driving, that it seems unstoppable, like the attack of the shark,” Williams explained. This inexorable backing allowed Spielberg to build that outright tension throughout his movie. And here’s another thing, when Spielberg heard it, he laughed at first because he thought it too simple. Let’s be honest, it goes E-F-E-F. Put yourself in the moment; the great director comes to Williams’ home or office, like in the video for ET. He lines up the film on the projector, turns down the lights and prepares to hear the music that his friend and composer has spent the past few weeks working on. Then he hears E-F…. E-F… E-F-E-F-E-F-E-F and Williams turns and looks at him. That must have taken some stones! And, as a great example of being a creative and following your own path, it worked! It didn’t just work, it’s become the most instantly recognizable them in the history of cinema!

Indeed, here’s some trivia for you. Spielberg himself can be heard playing on the soundtrack itself! Earlier in the movie, a high-school band is playing on a street parade, and Williams needed to record a terrible-sounding rendition with his orchestra. Spielberg, having played clarinet in his high-school band, joined the orchestra to record the music for that scene and helped to make it sound rather amateurish!

That’s why I love John Williams. He has consistently managed to make our movies infinitely better with his music. I haven’t even begun on “Jurassic Park” – the moment where Dr Grant first catches sight of the dinosaurs, a species that he has studied through their fossils for his whole life and now sees them in the flesh, something seemingly impossible and unimaginable. We just hear this sigh in the orchestra that is both comforting and majestic. It’s incredible.

JURASSIC PARK

One key aspect of the score is Williams’s use of bells tinkling in the upper register creating a childlike awe that we all experience the first time we see a dinosaur. We are all little Timmy and Dr Alan Grant when that first Brachiosaurus appears – this was the a convincing use of CGI in a world of stop motion – we are witnessing something that we thought was impossible. John Williams not only captures our childlike innocence, but also the majestic grandeur of these humongous creatures IN ONE THEME! Moreover, when we learn that the sound design team built the T-rex’s roar from the sounds of a baby elephant mixed with a walrus, then it is no wonder that his score had to match it for richness and complexity. However, it is relatively simple in it’s conception; the melody to this theme is based largely on a simple three-note motive (for those of you out there who are musically minded – B-flat, A, B-flat make up the first few breath notes before the whole theme appears).

My favorite piece of trivia about this piece comes from Spielberg who was receiving taped recordings of the theme whilst he was directing Schindler’s List and said that on his way to set, he would put the music on to cheer him up before tackling the emotional gut-punch that he was about to be dealt with the subject matter.

INDIANA JONES

Try playing the opening section of “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” when River Phoenix plays a young “Indy” trying to get a golden cross from the clutches of tomb raiders and into a museum. Having been fortunate enough to attend a John Williams concert in which Steven Spielberg was the guest compere for the evening, the latter introduced this notion – that 10 minute sequence, although filled with action, humor and several nods to Indiana Jones hallmarks, passes incredibly slowly when played without the iconic soundtrack. That is what the music does. It takes the incredible visuals and adds tension, emotion, angst. It uses the dark foreboding of the lower strings and brass when things look bleak, the high pitched percussion and violins when funny things happen to the clumsy villains and the whole orchestra performing the famous Indiana Jones theme when our hero is on top.

There is no doubt in my mind that the final 10 minutes of “ET-The Extra Terrestrial” are probably the most spectacular pieces of cinema there have ever been. In the video below we see the beloved composer with his friend and (by his own admission) the man he calls boss, talking through a “Call” and “Response” of the ET theme. The irony is not lost in that the theme surrounds the subject matter of an alien being trying to contact home and waiting for a “response” of his own. However, deeper than that, something that makes John Williams stand out from the majority of other movie soundtrack composers are his use of Leitmotif.

With Leitmotif, Williams can announce the arrival of a plethora of characters throughout a movie before they even appear on the screen. Moreover, he can convey the mood of that character through the key that that leitmotif is played in – famously with the Luke theme in Star Wars that modulates with the character’s internal struggle with the dark side. In Star Wars alone there are 55 leitmotifs – bits of melody repeated in the scores evoking particular characters, places, or relationships. You are listening to music whose roots lie in opera from the 19th Century! Leitmotif goes back to the times of Richard Wagner!

STAR WARS

Serendipitously, it proves my point that John Williams is the leitmotif king in that the above video contains the majority of Williams’ themes for individual characters. Most notably, Darth Vader’s Imperial March is the ultimate prophesier of doom (with the theme itself being associated with the boss on my phone since I started working here – don’t tell Shane). When this theme first appears in Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back it is when the Imperial fleet descend on the rebels. Most interesting is that it signals Vader’s ship. Before we even see the black helmeted anti-hero, we are welcomed into a world of foreboding by this music and, as audience members, await his presence on the screen like Michael Myers in Halloween or Anton Chigurh in No Country For Old Men – the terror begins with the music and builds us into an uncomfortable fervor until eventually it is broken by the deep breathing, black clothed Vader.

However… (and this is a great piece of trivia for all of you Star Wars fans) Vader had another theme from A New Hope (Episode 4) that disappeared. The team over at IGN.com analyzed the music from the original leitmotif associated with Vader that sounds equally ominous, but nowhere near as catchy.

The Imperial March owes its roots to classical music with the theme being based on the well known funeral march from Chopin’s Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor

and on “Mars, the Bringer of War” by Gustav Holst.

Like the character that Williams is trying to portray (and I suppose the evil Empire) as a whole, Williams wanted to create a theme that symbolized control, power, tyranny and oppression. To give the theme it’s due diligence, it was composed in 1980, but has been used in every single Star Wars movie (including the Star Wars Story movies such as Rogue One and Solo) since!

ET

Finally, ET is one of the themes of John Williams that took my breath away above all others – in particular the final 10 minutes of the movie which are, to be blunt, the finest piece of movie soundtrack composition that I think we will ever hear. 10 whole minutes of solid music accompanying a group of boys helping their alien friend to escape from the government confinement, leading the cops on a chase across Los Angeles to get him to the meeting spot where he can return to his home planet. After several attempts were made to match the score to the film, Spielberg took the film off the screen and encouraged Williams to conduct the orchestra the way he would at a concert. He did, and Spielberg slightly re-edited the film to match the music, which is unusual since normally the music would be edited to match the film. The result was Williams winning the 1982 Academy Award for Best Original Score.

Those final 10 minutes are what movies are all about – that is why WE do it. They are perfection.

Here is the greatest honor that I can do the John Williams soundtracks, I can’t imagine the greatest movies of my lifetime without them and do you know what? I don’t want to.

Hurlbut Academy works exclusively with Musicbed who provide us with all of our soundtracks for our lessons and sizzle reels. https://www.musicbed.com